Births of a Nation, Redux

Surveying Trumpland with Cedric Robinson

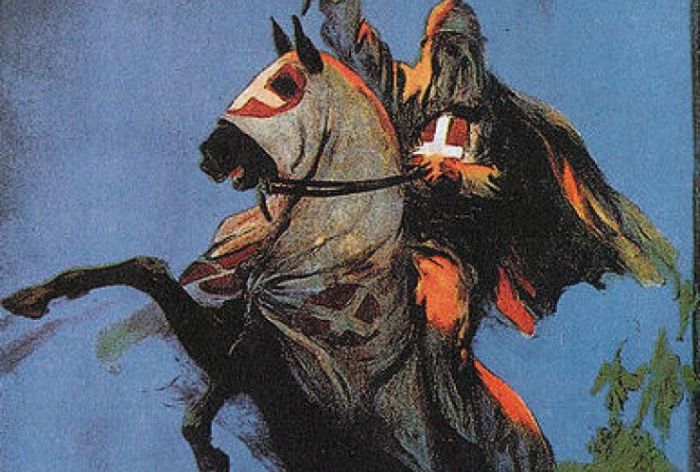

Image: A poster for Birth of a Nation (1915)

November 5, 2020

I wrote the following essay, “Births of a Nation: Surveying Trumpland with Cedric Robinson,” in the wake of Trump’s 2016 victory, but it could have been written today—two days into a still unsettled presidential election; two days of witnessing frenzied, nail-biting, soul-searching Democrats wondering what happened to the blue wave and why 68 million people actually voted for Trump; two days of threats from the White House that they will fight in the courts and in the streets before giving up power. And today Cedric Robinson, pioneering scholar of what he called the “Black Radical Tradition,” would have celebrated his eightieth birthday.

Today Cedric Robinson would have celebrated his eightieth birthday. What Robinson identified as “the rewhitening of America” a century ago is what we’re seeing play out today.

The lessons I took from Cedric in the aftermath of Trump’s election still stand: our problem is not polling, or the failure of Democrats to mobilize the Black and Latinx vote (they came out, often at great risk to their health and safety), or a botched effort to reach working-class whites with a strong, colorblind class-based agenda. What Robinson identified as “the rewhitening of America” a century ago is what we’re seeing play out today.

But before reviving the tired race-versus-class debate, pay attention: Robinson was making an argument about racial regimes as expressions of class power and how racism undergirds class oppression. As I quoted Robinson before: “White patrimony deceived some of the majority of Americans, patriotism and nationalism others, but the more fugitive reality was the theft they themselves endured and the voracious expropriation of others they facilitated. The scrap which was their reward was the installation of Black inferiority into their shared national culture. It was a paltry dividend, but it still serves.” (The emphasis is mine.)

What we’ve seen is the consolidation of a racial regime based—as are all racial regimes—on “fictions” “masquerading as memory and the immutable.” Trump is saving white suburban women from Black rapists and drug dealers who want to take their Section 8 vouchers out to gated communities. He’s protecting our borders from “illegals” who have no claims whatsoever to this white man’s country. He’s shielding the nation from wicked critical race theorists and Howard Zinn with “patriotic education.” He responds to the assault on white supremacist mythologies by defending Confederate monuments. He dispatches federal military forces to crush antiracist protests and declares Kyle Rittenhouse a patriot for killing two unarmed Black Lives Matter protesters. And he dusts off the tried and true strategy of labeling all challengers to the regime “communists and socialists.” (When Biden brags “I beat the socialists!” and “I am the Democratic Party,” he plays right into the regime’s fictions—he is the neoliberal moderate taking back the country from rioters, fascists, and socialists.)

We keep telling ourselves that Trump was elected as a backlash to a Black president, but really he was elected as a backlash to a Black movement. President Obama presided during the killing of Mike Brown, Tamir Rice, Tanisha Anderson, Philando Castile, Alton Sterling, Freddie Gray, Sandra Bland—ad infinitum. It was the mass rebellion against the lawlessness of the state—in Ferguson, in Baltimore, in Chicago, in Dallas, in Baton Rouge, in New York, in Los Angeles, and elsewhere—that prompted Trumpian backlash.

We keep telling ourselves that Trump was elected as a backlash to a Black president, but really he was elected as a backlash to a Black movement. Fear and racism feed off of insecurity.

The massive vote for Trump and his fascist law-and-order rhetoric should also be seen as a backlash to a movement. Some of us believed Black Spring rebellion in the wake of the murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Ahmad Arbery signaled a national reckoning around racial justice. But rather than reverse the rewhitening of America, our struggles catalyzed and concretized the racial regime’s explicit embrace of white power. Once again, an unstable ruling class drapes itself in white sheets, puts on its badge and brings out its guns. Fear and racism feed off of insecurity. And in the face of a global pandemic, joblessness, precarity, and an economy on the verge of collapse, this paltry dividend still serves.

If we’d paid attention, we wouldn’t have expected a Biden landslide or a blue wave ripping the Senate from Kentucky’s Mitch McConnell grip. It is not a coincidence that Louisville is on fire over the murder of Breonna Taylor and countless others who died at the hands of police in McConnell’s state. Kentucky has always been a battleground. California is too, and we’re not necessarily winning. Voters just defeated affirmative action, rent control, and the labor rights of gig workers. And despite some important victories, California delivered a lot of votes to Trump. We need to face the fact that our entire country, and the world, is a battleground. Trump and McConnell have succeeded in packing the Supreme Court with reactionaries. Trump’s backers still run the Senate. Gun-toting men and women in red hats stand outside vote-tabulating centers, threatening to do whatever is needed to secure a Trump victory. They yell “stop the count.”

Even with a Biden victory, the failure of the blue wave will be attributed in part to a certain kind of identity politics—Black and Latinx voter turnout less than what was expected—or to the militancy of antiracist protests, or to left-leaning candidates who scared off white moderates by pushing for single-payer healthcare and a Green New Deal. We should not see these as problems for legitimate Democrats. We’ve been witnessing authentic small-d democracy in action. In the streets we’ve seen a movement embrace Black, Brown, and Indigenous people, queer feminism, and a horizontal leadership model that emphasizes deliberative, participatory democracy.

We have an electoral college, battleground states, and voter suppression because the U.S. political order was built on anti-democracy.

This is the democracy Cedric Robinson insisted we embrace. He reminded us that the U.S. political order was built on anti-democracy, a theory of so-called enlightened governance that excludes the popular classes. This is why we have an electoral college, why we have battleground states, and why voter suppression was built into our country’s DNA. As I wrote three years ago, “today’s organized protests in the streets and other places of public assembly portend the rise of a police state in the United States. For the past five years, the insurgencies of the Movement for Black Lives and its dozens of allied organizations have warned the country that unless we end racist state-sanctioned violence and the mass caging of black and brown people, we are headed for a fascist state.”

We’re already here. And there is no guarantee that a Biden-Harris White House will succeed in completely reversing this trend. Nor should we expect presidents and their cabinets to do this work. That would put us back where we started—with tacit acceptance of the principles of anti-democracy.

Cedric’s words from exactly twenty years ago still haunt: “For the moment . . . an unelected government has seized illegal powers. That must be opposed with every democratic weapon in our arsenal.”

Happy Birthday, Dr. Robinson.

March 6, 2017

Cedric Robinson was fond of quoting his friend and colleague Otis Madison: “The purpose of racism is to control the behavior of white people, not Black people. For Blacks, guns and tanks are sufficient.” Robinson used the quote as an epigraph for a chapter in Forgeries of Memory and Meaning (2007), titled, “In the Year 1915: D. W. Griffith and the Rewhitening of America.” When people ask what I think Robinson would have said about the election of Donald Trump, I point to these texts as evidence that he had already given us a framework to make sense of this moment and its antecedents.

Robinson’s work—especially his lesser-known essays on democracy, identity, fascism, film, and racial regimes—has a great deal to teach us about Trumpism’s foundations, about democracy’s endemic crises, about the racial formation of the white working class, and about the significance of resistance in determining the future.