The argument has often been used to diminish the scale of slavery, reducing it to a crime committed by a few Southern planters, one that did not touch the rest of the United States. Slavery, the argument goes, was an inefficient system, and the labor of the enslaved was considered less productive than that of a free worker being paid a wage. The use of enslaved labor has been presented as premodern, a practice that had no ties to the capitalism that allowed America to become — and remain — a leading global economy.

But as with so many stories about slavery, this is untrue. Slavery, particularly the cotton slavery that existed from the end of the 18th century to the beginning of the Civil War, was a thoroughly modern business, one that was continuously changing to maximize profits.

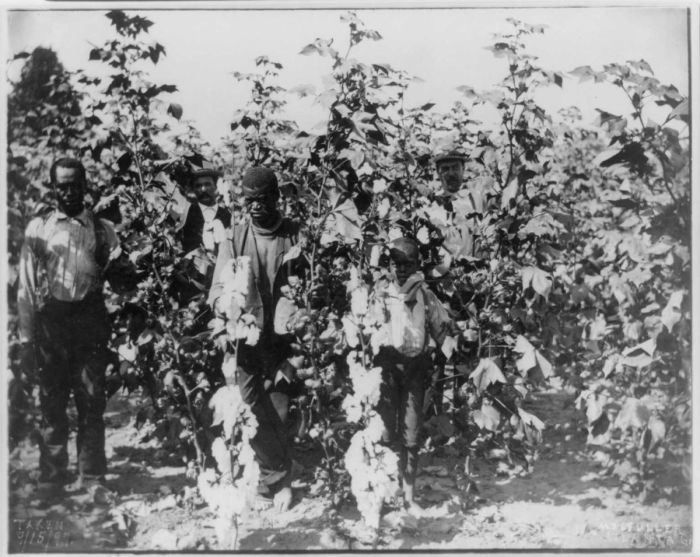

To grow the cotton that would clothe the world and fuel global industrialization, thousands of young enslaved men and women — the children of stolen ancestors legally treated as property — were transported from Maryland and Virginia hundreds of miles south, and forcibly retrained to become America’s most efficient laborers. As they were pushed into the expanding territories of Mississippi and Louisiana, sold and bid on at auctions, and resettled onto forced labor camps, they were given a task: to plant and pick thousands of pounds of cotton.

The bodies of the enslaved served as America’s largest financial asset, and they were forced to maintain America’s most exported commodity. In 60 years, from 1801 to 1862, the amount of cotton picked daily by an enslaved person increased 400 percent. The profits from cotton propelled the US into a position as one of the leading economies in the world, and made the South its most prosperous region. The ownership of enslaved people increased wealth for Southern planters so much that by the dawn of the Civil War, the Mississippi River Valley had more millionaires per capita than any other region.

In recent years, a growing field of scholarship has outlined how America — through the country’s geographic growth after the American Revolution and enslavers’ desire for increased cotton production — created a complex system aimed at monetizing and maximizing the labor of the enslaved. In the cotton fields of the Deep South, this system rested on the continuous threat of violence and a meticulous use of record-keeping. The labor of each person was tracked daily, and those who did not meet their assigned picking goals were beaten. The best workers were beaten as well, the whip and other assaults coercing them into doing even more work in even less time.

As overseers and plantation owners managed a forced-labor system aimed at maximizing efficiency, they interacted with a network of bankers and accountants, and took out lines of credit and mortgages, all to manage America’s empire of cotton. An entire industry, America’s first big business, revolved around slavery.

“The slavery economy of the US South is deeply tied financially to the North, to Britain, to the point that we can say that people who were buying financial products in these other places were in effect owning slaves, and were extracting money from the labor of enslaved people,” says Edward E. Baptist, a historian at Cornell University and the author of The Half Has Never Been Told: Slavery and the Making of American Capitalism.

Baptist’s book came out in 2014, the same year that essays like the Ta-Nehisi Coates’s “The Case for Reparations” and protests like the Ferguson Uprising would call attention to injustices in wealth and policing that continue to affect black communities — injustices that Baptist and other academics see as being closely connected to the deprivations of slavery. As America observes 400 years since the 1619 arrival of enslaved Africans to the colony of Virginia, these deprivations are seeing increased attention — and so are the ways America’s economic empire, built on the backs of the enslaved, connects to the present.

I recently spoke with Baptist about how cotton slavery transformed the American economy, how torture, violence, and family separations were used to maximize profits, and how understanding the economic power of slavery impacts current discussions of reparations. A transcript of our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

P.R. Lockhart

When you talk about the sort of myth-making that has been used to create specific narratives about slavery, one of the things you focus on most is the relationship between slavery and the American economy. What are some of the myths that get told when it comes to understanding how slavery is tied to American capitalism?

Edward E. Baptist

One of the myths is that slavery was not fuel for the growth of the American economy, that it actually the brakes put on US growth. There’s a story that claims slavery was less efficient, that wage labor and industrial production wasn’t significant for the massive transformation of the US economy that you see between the time of Independence and the time of the Civil War.

And yet that period is when you see the US go from being a colonial, primarily agricultural economy to being the second biggest industrial power in the world — and well on its way to becoming the largest industrial power in the world.

Another myth is that slavery, in and of itself as an economic system, was unchanging. We fetishize machine and machine production and see it as quintessentially modern — the kinds of improvements in production and efficiency that you see from hooking up a cotton spindle to a set of pulleys, which are in turn pulled by a water wheel or steam engine. That’s seen as more efficient than the old way of someone sitting there and doing it by hand.

But you can also get changes in efficiency if you change the pattern of production and you change the incentives of the labor and the labor process itself. And we still make these sorts of changes today in businesses — the kind of transformations that speed up work to a point where we say that it is modern and dynamic. And we see these types of changes in slavery as well, particularly during cotton slavery in the 19th-century US.

The difference, of course, is that this is not the work of wage workers or professional workers. It is the work of enslaved people. And the incentive is not “do this or you’ll get fired” or “you won’t get a raise.” The incentive is that if you don’t do this you’ll get whipped — or worse.

The third myth about this is that there was not a tight relationship between slavery in the South and what was happening in the North and other parts of the modern Western world in the 19th century. It was a very close relationship: Cotton was the No. 1 export from the US, which was largely an export-driven economy as it was modernizing and shifting into industrialization. And the slavery economy of the US South was deeply tied financially to the North, to Britain, to the point that we can say that people who were buying financial products in these other places were in effect owning slaves and were certainly extracting money from the labor of enslaved people.

So those are the three myths: that slavery did not cause in any significant way the development and transformation of the US economy, that slavery was not a modern or dynamic labor system, and that what was happening in the South was a separate thing from the rest of the US. . . .”

Read the full interview here: Source: How slavery became the building block of the American economy – Vox